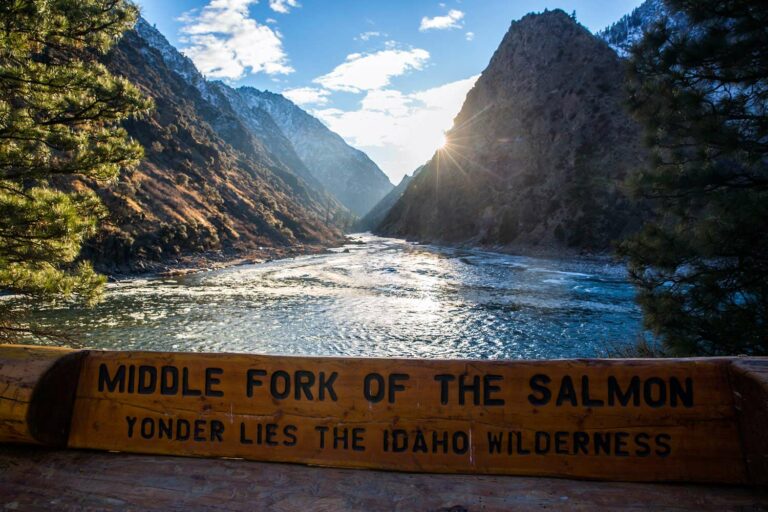

April 24th marks Arbor Day, and to celebrate we at Idaho River Journeys would like to introduce you to some of the most abundant, specialized, and awe-inspiring organisms you will encounter on any Middle Fork Salmon River trip: trees! From the towering and regal ponderosa pine to the humble and hardy mountain mahogany, each and every species of tree on the Middle Fork plays an integral role in the riparian ecosystem. Amazingly resilient, these trees face wildfire, wind events, landslides, and fierce winters. These constant threats contribute to creating some of the most highly-evolved, uniquely adapted plants you’ll ever see! So, whether you’re a city-slicker who’s camping for the first time or a wizened tree-hugger, the arboreal varieties found on the Middle Fork Salmon are sure to leave a wealth of reverence for the natural world. Here’s a list of nine species to appreciate on your next trip!

Ponderosa Pine

Pinus ponderosa

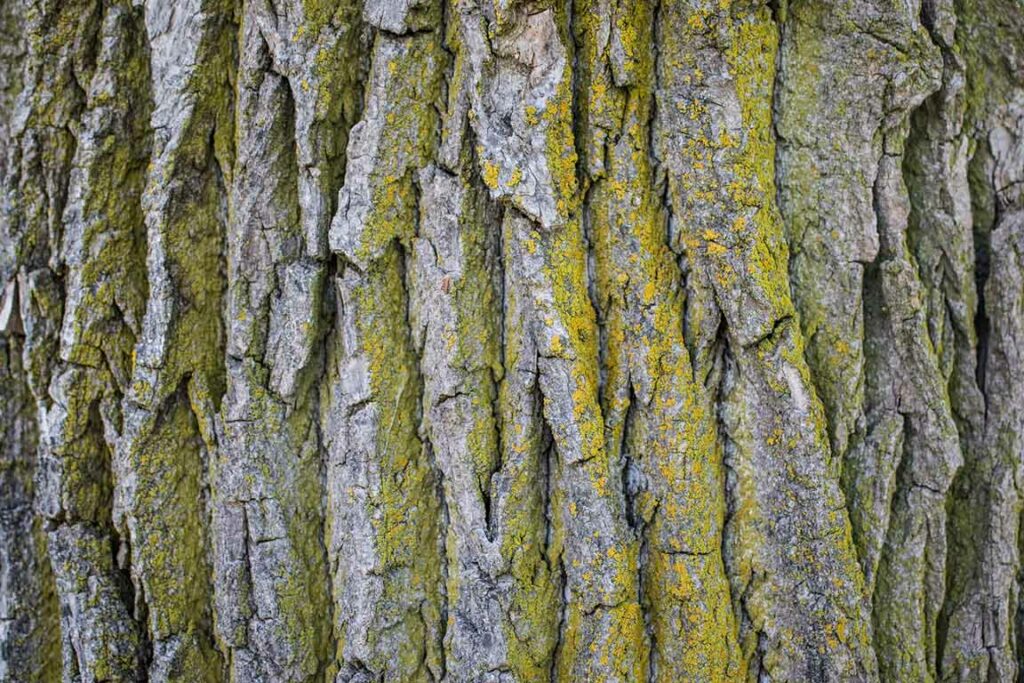

The ponderosa pine is the state tree of Montana and one of the most impressive trees you’ll see on the Middle Fork. Growing up to 150 feet tall, these behemoths have evolved remarkable adaptations to deal with the wildfires that frequent central Idaho’s forests. Also known by the fitting moniker of “yellow pine,” the ponderosa sports large, yellow pieces of bark that surround its trunk in a puzzle-like mosaic. When fires roar through the forest these bark plates fall off to shunt heat away from the essential vasculature inside. Additionally, the ponderosa sheds its lower branches as it matures to prevent flames from blazing up into its crown.

Lodgepole Pine

Pinus contorta

Preferring higher elevation slopes, these abundant conifers are impossible to miss on the first couple days of a Middle Fork trip. Dense stands of healthy lodgepoles blanket the upper reaches of the watershed, and in the miles preceding Pistol Creek rapid the aftermath of recent wildfires can be seen on full display. The juxtaposition of these live trees and those ravaged by fire provides a perfect illustration of the life-cycle of lodgepole pines and their dependence on fire to regenerate the species. With serotinous cones, the lodgepole relies on the high temperatures produced during significant wildfires to melt the resin sealing its cones shut. When this pitch is removed, the cones release seeds and the freshly scorched forest begins the process of renewal. This dependence on fire has made the lodgepole especially susceptible to problems stemming from anthropic fire suppression. By not allowing lodgepole forests to burn naturally, humans have disrupted this natural cycle, leading to overly dense stands with elevated fuel loads. This increased density has also supported the expansion of the mountain pine beetle in forests throughout the west, the effects of which can be seen on some sections of the Middle Fork.

Plains Cottonwood

Populous deltoides ssp. monilifera

Some of the largest deciduous trees on the Middle Fork, these hardwoods can grow up to 80 feet tall and live over 100 years! The cottonwood’s large, toothed leaves have a tendency to quiver in even the slightest breeze, making them easily recognizable from afar. A spiritually significant tree to some Native tribes, the cottonwood’s flowers, inner bark, and sap are all edible, and were used as both a lean food source and an astringent tea for treating gastric ailments. Perhaps the most interesting quality of the cottonwood is its reproductive strategy. It is a “dioecious” plant, meaning individuals are single sex; either male or female. This difference is most easily noted in the early spring when the tree flowers. Female trees produce flowers, or “catkins” that are green, and grow upon pollination to make seeds that are dispersed on the wings of its name-sake “cotton” tufts. Male trees on the other hand, produce purple catkins that provide pollen but do not produce seeds.

Mountain Alder

Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia

Another deciduous and dioecious tree, this birch thrives on conditions that other species struggle with. Also known as the thinleaf alder, this tree utilizes its shallow root system to colonize relatively difficult habitats like scree slopes and alluvial fans, and is commonly spotted on the Middle Fork taking advantage of these environments. A life-span of 60 to 100 years, these fast-growing alders grow in clumps that can reach heights of 40 feet or so. Close inspection of these bunches reveal smooth bark and ovate leaves up to four inches long by three inches wide.

Mountain Mahogany

Cerocarpus lendifolius

One of the most distinct looking trees on our list, the mountain mahogany is in fact not a mahogany at all; rather it is a member of the rose family. Semantics aside, the contorted, gnarled figure of the mahogany is commonly spotted in the lower reaches of the Middle Fork. Here it carves out its niche on rocky, gravelly slopes. Perfect firewood, the “Iron Wood” tree was also favored by Native people for its strength and durability, which lent itself well for use in bows, arrows and digging tools. Medicinally, the bark of the mahogany was commonly brewed into tea to fend off colds and other common ailments.

Rocky Mountain Juniper

Juniperus scopulerum

With a species name meaning “of the mountains,” the rocky mountain juniper is well adapted to the arid, mid-elevation climate of the lower Middle Fork. This smaller tree grows to only 30 feet or less, but can live an outstandingly long life. Some individuals have been aged to 1,500 years or more! Along with providing an important food and nesting source for many animals and birds, the juniper has long served a laundry list of medicinal purposes for Native people. Used to treat everything from fevers to arthritis, leaves and bark were traditionally boiled into a tea and consumed by afflicted individuals.

Rock Mountain Douglas Fir

Pseumdotsuga menziesii ssp. glauca

Perhaps best known as a popular Christmas tree, the Douglas fir is named in honor of Scottish botanist David Douglas who first recognized its extensive distribution in the early 1800s. Found on the Middle Fork, the rocky mountain variety is a medium-sized evergreen, usually growing to around 70 feet tall. An important food source for animals, the fir is browsed by elk, deer and sheep who feed on its twigs and foliage; as well as chipmunks, mice and other small animals who feed on cones that fall to the forest floor.

Engelmann Spruce

Picea engelmanii

German botanist George Engelmann’s namesake spruce is one of the highest elevation trees found in central Idaho, commonly growing at or near the alpine tree line. Reaching heights up to 100 feet tall, it is commonly found associated with the subalpine fir, another hardy evergreen that thrives in the cold, harsh climes of upper elevation slopes. Several characteristics make the Engelmann spruce unique and especially susceptible to the climatic factors of wind and drought. Foremost, the Engelmann’s shallow root system makes it prone to wind-fall in blustery conditions. This downed wood thus increases the fuel load for future fire events and also makes forests more vulnerable to spruce beetle invasion. Additionally, years of drought and above average heat can wreak devastating effects on spruce saplings, whose roots struggle to gain a footing in dry, hot conditions. Hardships notwithstanding, the Engelmann is incredibly resilient, and can live to be 500 years or more, with some individuals aged to 850 years!

Whitebark Pine

Pinus albicaulis

Another high-elevation species, the whitebark pine is often found near tree-line as “krummholz”. From the German for “crooked wood,” these stunted structures have been contorted, deformed and dwarfed by a lifetime exposed to the elements in the alpine. In more favorable conditions, the whitebark pine can grow up to 90 feet or so. Containing five needles per fascicle, the whitebark can be distinguished from lodgepole and ponderosa pines, which possess bundles of two and three needles, respectively. Of these three pine species, the whitebark is also the most threatened, having seen severe population declines in recent decades due to mountain pine beetles, increased fire suppression and climate change. An important food and habitat source for many critters, the cones of the whitebark pine are commonly stored by squirrels in their middens, which are in turn often raided in the fall by hungry bears looking to fatten up on seeds before hibernating.