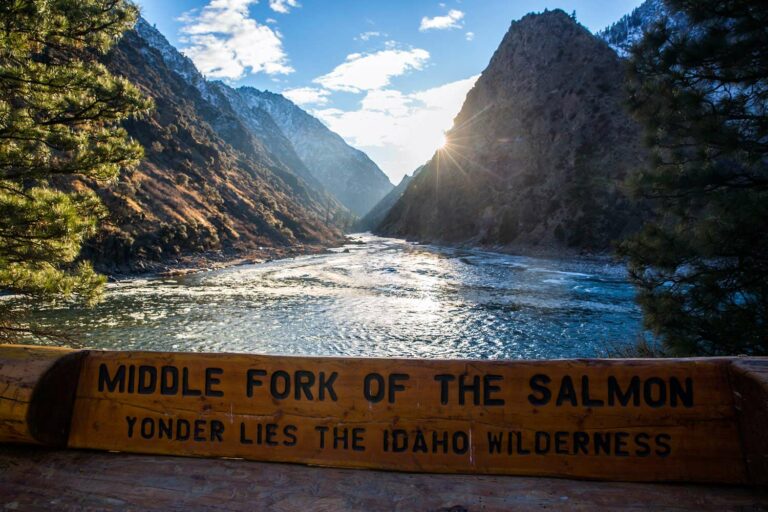

In the Spring of 2022, Libby Tobey, Brooke Hess, and Hailey Thompson set out on a 1,000-mile kayaking expedition following the natural migration path of anadromous fish from the rivers of central Idaho to the Pacific Ocean. The “Source to Sea” goal was to is to connect, educate, and engage communities through conversations and storytelling in a call to action around Idaho’s endangered chinook, sockeye, and steelhead populations. After completing the 1000-mile journey, Libby immediately started guiding on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. After her season ended on the Middle Fork, Libby wanted to provide a brief summary of her trip, as well as the current state of salmon and the removal of the four Lower Snake dams.

Source to Sea – By Libby Tobey

The Lower Snake River dams (LSRDs) are the centerpiece of a decades-long battle for the river system’s thirteen wild salmon populations, all of which are federally listed as threatened or endangered. These endangered salmon species include the Chinook and Sockeye that return to spawn in Idaho’s Middle Fork, South Fork, and Main Salmon Rivers.

Over the course of their life cycle, Idaho salmon travel thousands of miles– from their birthplace in the headwaters to their ocean homes in locations as far-flung as the Aleutian Islands. They return as adults to spawn and die, bringing nutrients from the sea to the mountains of Idaho: an annual influx upon which the whole ecosystem depends. Their annual return or “run” is endangered today by many outside pressures, including hydropower dams like those on the Snake whose stagnant reservoirs have replaced the free-flowing water that once aided the salmon’s migration. The dams also exacerbate many of the pressures that climate change places on migrating fish, like dangerously warm water temperatures in reservoirs. For an idea of how close to extinction Idaho’s salmon are: in 2021, a total of four wild Sockeye returned to Redfish Lake to spawn. But while at first glance the state of the salmon appears bleak, calls to breach the dams have been approaching what may soon prove to be a critical mass, raising questions of what we as river lovers, guides, and advocates can do to help.

The answer, it turns out, can be (mostly) as simple as doing and sharing what we love. Or, at least, that’s what some close friends and I set out to do in April of this year. Beginning in the headwaters of the Salmon River, our goal was to ski tour and paddle roughly 1,000 miles to the Pacific Ocean, using the expedition as a conservation platform to get people engaged with the issue– and help build momentum towards the breaching of the LSRDs. Over 2.5 months, we connected with local communities all along our route to talk about salmon, hear people’s stories, and write pro-breaching postcards to Congress. We paddled through blizzards, portaged five of the eight dams that stand between Idaho and the ocean, and ate more dehydrated meals than any of care to remember.

But, ultimately, did the Grand Salmon expedition serve the purpose we hoped it would? And what has happened in the months since we paddled out into the Pacific Ocean? In late August, Patty Murray and Jay Inslee of Washington finalized a draft report on regional salmon recovery that recognized swift breaching of the LSRDs as the most effective way to protect and restore salmon. Shortly thereafter, a report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) outlined similar conclusions. These reports, which represent increasing state and federal recognition of the dire conditions wild salmon are facing, are a significant step towards getting the dams breached; the final approval for which must come from a Congressional vote.

So what comes next? And what can our river and salmon-loving friends do right now?

- VOTE!! Wherever you are, vote for environmentally conscious candidates that will in turn put their votes behind protections for salmon and free-flowing rivers.

- Pressure your returning or incoming Congresspeople to remove the Lower Snake Dams. Look to conservation leaders like Idaho Rivers United, American Rivers, and American Whitewater for effective, straightforward ways to do this.

- Extra credit for submitting a comment on the Forest Service’s updated DEIS for the proposed Stibnite Gold Mine, which threatens critical salmon spawning habitat in the South Fork Salmon River. Advocating for a moratorium on this mine was also a central goal of the Grand Salmon project. Comments on the updated DEIS are due by 1/10/2023.

- Finally, get out on your rivers…! We tend to care most about –and take action for—the places we feel personally connected to. Get out and float, fish, or hike. Get to know the rivers in your backyard. Then get out there and speak up for them!

Ultimately, my greatest personal takeaway from the Grand Salmon is the strong case for hope in a situation that feels largely grim. Yes, Idaho’s salmon face a looming threat of extinction. Yes, the landscapes and people that depend on them are threatened, too. But the salmon aren’t gone, and in one of nature’s most awe-inspiring displays of tenacity, they continue to return against the increasing odds. Given half a chance, their populations can and will bounce back—let’s not waste any time in giving them that chance.